It’s worth reflecting how badly things can go, even when you have major advantages in life.

Donald Cowart, Jr. had a life that looked fairly bright looking forward and backward in 1973. He came from what was as best I could tell a prosperous and loving American middle-class home. He was a star athlete in high school who went on to a good college and then did a tour of duty as a U.S. Air Force pilot in Vietnam. (The photographs below are screencaps from a documentary film about Cowart and his experiences called Dax’s Case, and I would like to thank Sister Y and Rob Sica for their generously helping me to locate a copy.)

Donald Cowart as a high school student

...and as a pilot

In 1973, Cowart was contemplating his future as either a commercial airline pilot or in real estate. He and his father went to inspect a parcel of land in East Texas, propane had leaked from a pipeline and settled in a nearby creekbed. Their attempt to start the car ignited the propane. Cowart was so severely burned and in such pain that when a nearby farmer came to render aid, Cowart begged him for a gun so that he could end his own life. Instead, he was collected by an ambulance (so extensive were Cowart’s injuries that the crew had to lift him by his belt). It was the beginning of a decade-long ordeal of Cowart. He was blind, helpless (he lost all of his fingers) and terribly disfigured. But it was his treatment that really seems to have been the worst. Here is part of an account given by Cowart in a lecture he gave at the University of Virginia (for which you can also find video here.)

Some techniques were used at that time…daily tankings or almost daily tankings in the Hubbard tank where they did a debreeding process using brushes, using sharp instruments like scalpels, something of that nature to brush away and cut away the dead and infected tissue. It felt like being…it felt like I was being skinned alive. In the beginning, it took several people to hold me down…my arms, my legs…and I could still overcome them sometimes. And sit up and they would eventually overcome me and push me back down. They used a topical antibiotic. They rotated the topical antibiotics. One of them burned like hell. It is called Sulfamylon. A lot of burn wards and burn doctors…tell me, you know, we quit using it, Sulfamylon now in our burn ward because we consider it barbaric. It is like having alcohol poured over raw flesh except it burns more and it burns longer.

[…]

Another one of the treatments was the use of wet to dry bandages. I had no flesh from right about here down to the top of where my boots were that I was wearing during the fire. It was just raw flesh. They would take bandage rolls, soak them with saline solution. And then take the wet bandage and just wrap them like a mummy all the way from my hips down to almost to my ankles. They allowed those bandages to dry so they would adhere to the raw flesh without any skin on it, and then unroll the bandages. That felt like I was being skinned alive. And that is another practice that many hospital people that have worked around the burn wards have said we don’t do that anymore because we consider it barbaric.

Cowart in treatment

Cowart repeatedly asked to be allowed to die or to leave the hospital, requests which we repeatedly denied. He was forcibly treated against his will.

Cowart eventually recovered from his injuries and became an attorney, businessman, and advocate for patient autonomy. He now has a quality of life he regards as decent (and also changed his name to “Dax.”) Bu he has always maintained that in spite of this fact, he should have been allowed to die.

Dax Cowart being interviewed after his recovery

Dax’s “case” is often thought of as an important one in medical ethics, though it isn’t that for me (to me it’s just a no-brainer that Cowart should have been allowed to die, and indeed that he should have been given a lethal overdose of fast-acting barbiturates if he so requested). To me it’s more an opportunity to reflect on how bad things can easily be.

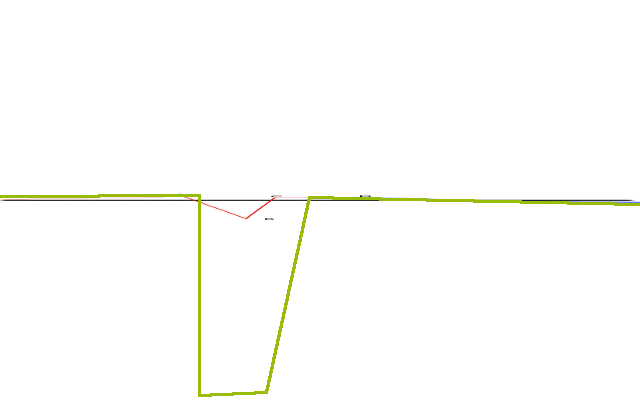

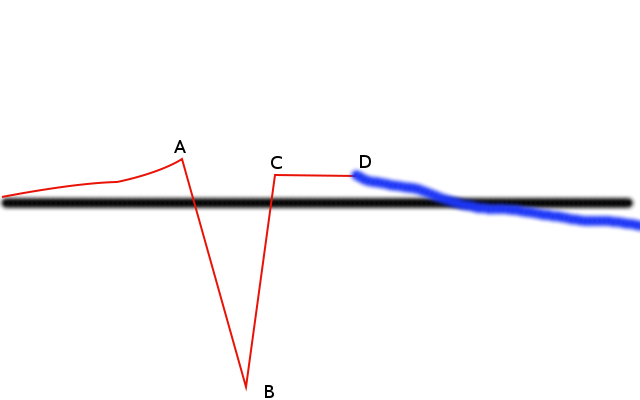

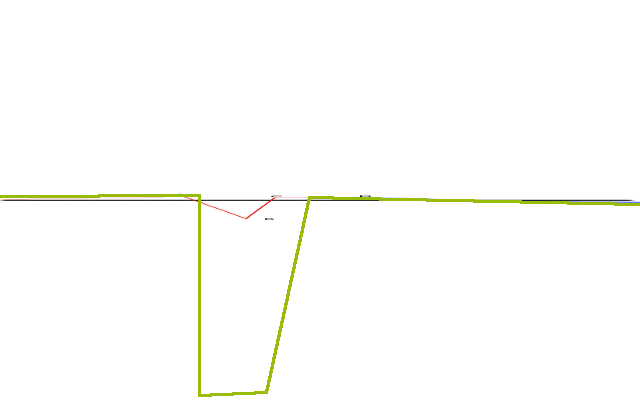

I’ve tried imagining a “shape of the life” graph for Dax Cowart. I don’t want to pretend that this is terribly quantitatively precise — it’s a very rough effort. The black line down the middle is a hedonic zero. The red and blue in the middle are a compressed version of the shape-of-life that I did for myself a little while ago. Me and my petty sorrows pretty much hug the zero in this representation. The green line is my I-hope-rational reconstruction of Dax Cowart: pretty good up until his accident, then falling off a cliff into an abyss of suffering from which he eventually recovers.

Another reflection — there’s an argument for antinatalism here, because Dax Cowart could be anyone, and his life could be anyone’s. Terrible accidents erupt into lives all the time. Have a child, and risk them happening to them, and you yourself risk becoming the analog of this woman:

Ada Cowart, Dax's mother

Mrs. Cowart insisted on Dax’s treatment against his will. Let me note: although in doing this I think she was doing something dreadfully wrong, I view her position as tragic rather than wicked. I have no reason to think of Ada Cowart as anything other than a perfectly kind and decent person (and, of course, his mother) making decisions in a horrible situation. I will not pretend that, were I somehow to find myself in an analogous situation, that I would do any better than she. Again, a reflection that what Ada Cowart did is yet another example of how evolution is not our friend (parental love trumps the imperative to end suffering) and, in Mrs. Cowart’s case, an example of the moral corruption foisted on us by Christianity (she did want to keep Dax alive in his sufffering so that he could “make his peace with God.”)

Even if one is not convinced by Benatar’s asymmetry, even if one thinks that the good things in life somehow “make up for” suffering, one is obliged to ask oneself, how many “good” lives would there have to be to somehow make up for what Dax Cowart had to undergo?