There are many barriers to suicide. Some of these are formidable external ones, ably elucidated and explored by writers like Sister Y. These barriers include the comparative lack of access to swift and painless means of killing oneself and a society committed to interventions — sometimes brutally coercive interventions — to prevent suicide. Others, I think more formidable, exist internally. People are, in general, very very afraid of death. We normally think that the worst legal penalty we can inflict on anyone is death. Even very old and sick people who will soon be dead anyway undergo painful, costly treatments to stave off death. Militaries the world over know that you need extensive indoctrination, training, and the threat of social shaming to get soldiers to go into battle where they will face death (and even then, they usually have someone in back of the line who will shoot you if you try to run away). People hate to even think about death, and when they do, it deranges their minds.

I strongly suspect that our fear of death is something hard-wired in our minds and thus very difficult to overcome. Organisms that were really really motivated to survive in the nasty world full of predators and parasites and starvation would b a lot better at reproducing themselves than those that weren’t. It’s nasty that this is achieved through so much fear, but natural selection doesn’t care how miserable you or anyone else is. It only “sees” the production of new organisms. Evolution is not your friend.

In spite of the probable hard-wiring of this fear of death, it seems at least thinkable that some people overcome it. David Hume might have been one such for real. James Boswell, visiting Hume on his deathbed in 1776 reports a surprisingly cheerful and even witty philosopher who jested about how we would have to have infinite universes in which to put everyone and where “…that the trash of every age must be preserved.” More seriously, Hume advanced an argument found in Lucretius to the effect that “…he was no more uneasy to think he should NOT BE after this life, than that he HAD NOT BEEN before he began to exist.” (When Boswell reported Hume’s conduct to Samuel Johnson the latter was (predictably) immensely irritated “Sir, if he really thinks so, his perceptions are disturbed; he is mad: if he does not think so, he lies. He may tell you, he holds his finger in the flame of a candle, without feeling pain; would you believe him? When he dies, he at least gives up all he has.” Such Christian charity!)

In spite of the probable hard-wiring of this fear of death, it seems at least thinkable that some people overcome it. David Hume might have been one such for real. James Boswell, visiting Hume on his deathbed in 1776 reports a surprisingly cheerful and even witty philosopher who jested about how we would have to have infinite universes in which to put everyone and where “…that the trash of every age must be preserved.” More seriously, Hume advanced an argument found in Lucretius to the effect that “…he was no more uneasy to think he should NOT BE after this life, than that he HAD NOT BEEN before he began to exist.” (When Boswell reported Hume’s conduct to Samuel Johnson the latter was (predictably) immensely irritated “Sir, if he really thinks so, his perceptions are disturbed; he is mad: if he does not think so, he lies. He may tell you, he holds his finger in the flame of a candle, without feeling pain; would you believe him? When he dies, he at least gives up all he has.” Such Christian charity!)

So maybe terror at death is not inevitable, though most of us are still probably a lot more like Johnson than Hume in our inner makeup with respect thereto. Maybe we need a little pharmacological help.

Imagine a drug — call it epicurazine — distributed through the air or water so that all who encounter it achieve Hume’s equanimity in the face of their own deaths. Suppose, though that this is epicurazine’s only effect — it doesn’t make them calmer or happier about anything other than the prospect of their deaths.

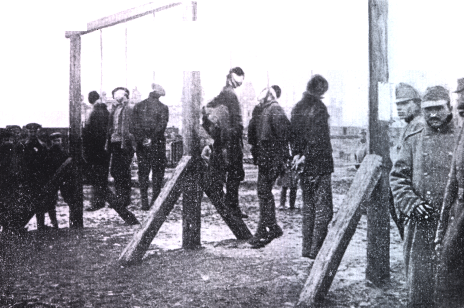

Then imagine further all the external barriers to suicide are dropped away. The priests are all deported and the psychiatrists are all locked up in the madhouses that they once ran and nembutal is available in ubiquitous vending machines.

As things stand, even in a world where the means of suicide are problematic and death a terror, suicide is still rather common. The NIMH estimates that in 2007 it was the tenth-leading common cause of death and that there are 11.3 successful suicides per 100,000 population.

In my counterfactual world, how much do you think suicide would increase? One order of magnitude? Two? Three?

(And we think our lives are…good?)