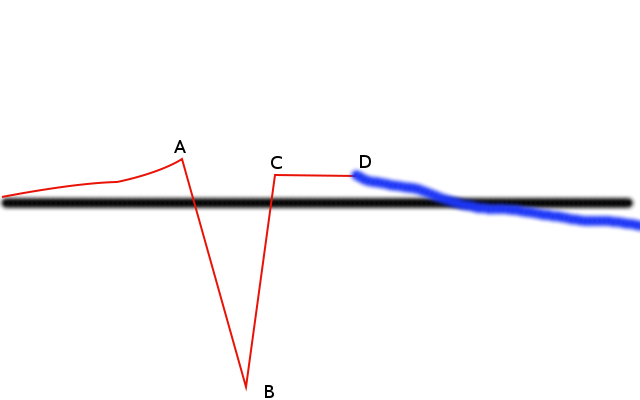

Over the past few weeks while I was neglecting blogging over here I came up with the probably-unwise idea of trying to draw the shape of my life in hedonic terms. I came up with this:

The fuzzy black line down the middle represents what for lack of a better term I would call a hedonic zero, and the red and blue lines represent my average tendencies at various part of my life. Above the line, life seemed worth it, and below it, not so much. I admit (with some shame) that it’s hard for me to make the concept of a hedonic zero very precise (which is why it is a fuzzy) line, but I (and, I fear) many of my readers have a sense of what it’s like to be below it. It is the mental state one’s in when one frequently wants out somehow. It might take the form of thought of suicide but it might be less active than that. It could be wishing one was dead (not the same as contemplating suicide, necessarily), or wishing that one had never been born. It might just mean fantasies of escape and deliverance. And probably lots of palliation, like drinking way too much and way too often.

Up until about 23 or 24 (Point A) life actually did seem pretty good, and then both my romantic career hopes did a long crash and burn, (Point B). Eventually I rebuilt. It was quite difficult and painful, but eventually life seemed sort of tolerable again by my early thirties (Point C) and has held steady more or less to the age I am now (Point D). From the fuzzy blue line projecting forward, I’m not all that sanguine about the future. It possible that things will go better. I’m not counting on it. It’s also possible that things will go much worse. There are hideous miseries associated with late-life cancers, bereavement at the loss of loved ones. Even at best, things will likely get worse. My energy will diminish, as will my ability to learn things, as will my attractiveness (such as it is). The presbyopia that began setting in at about the age of 40 will only get worse, even with good ophthamologic care, and in turn my ability to read comfortably — one of life’s real consolations — will erode over time.

There might be a point of controversy in this illustration in that I put point B so low below A. It’s a very rough form of quantification, of course. My best guess here is that I at a rough guess I’d be indifferent between a gamble of (0.9A or 0.1B) and a state of just barely finding life worth living.

A curious realization that attended this exercise is that, even if one rejects Benatar’s Asymmetry, I should still conclude that it would have been better to have painlessly winked out of existence sometime around the age of 23 rather than for me to be alive now, at least if one accepts any aggregation over one’s life as a measure of how well it has gone. Many people would find this conclusion depressing, but I do not. Sometimes I even find it a little liberating.

My point of presenting this result is not to wallow in self-pity. Indeed, it is something the opposite of that. I think that I have actually enjoyed unusual advantages in life. My family was not rich but my parents were very committed to giving their children such advantages as they could. I had enough natural cleverness to scholarship my way through a truly expensive and “elite” education. I have never been hungry, never had serious health problems, never gone to jail. Even at the end of my awful twenties I still had the resilience and resources to pull together and start over in a pretty good job. By the standards that measure unearned privilege in the rich, peaceful society I inhabit, I am a winner: white, straight, and male. (Well, okay, an atheist as well and that’ not generally so well received in many circles, but it’s easy to hide that and pass if that’s what you want to do.) I might still think that it would have been better to have perished at 23, but I come to this realization and still hold a conviction that many and perhaps most people have had worse lives than mine, not better ones.

If that’s true, then my life is a kind of argument for antinatalism.

5 Responses to “The shape of a life”

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.

Fascinating post, James. I can’t resist quoting from the Woody Allen piece I put up on my own blog a few days ago: “The best of lives are sad and tragic. The best of them.” I was also glad to finally see someone make the distinction between wishing one was dead and contemplating suicide.

I identify with a great deal of this – even timing and ages! I know better than to generalize from my own strange experiences, but I wonder how common this pattern is for our ilk, however defined?

The fact that lives like ours – with caring parents, many advantages, etc. – often turn out to be subjectively not worthwhile seems like a better argument for our kind of across-the-board antinatalism than the fact that so many lives seem objectively awful.

People becoming parents don’t seem to understand that it often doesn’t matter that much how good of a parent you are. The harm is done by having the child.

I also understand what you are talking about. I am 31 now, and I started to become less optimistic about life a few years ago. I am very disappointed in how my career has turned out so far, especially since I had very high expectations because of my educational background, and the great things it was supposed to bring me. I have been able to earn a decent living, but nothing compared to what I was hoping for. I think the other issue is when we are younger we believe we control our destiny and that we can make life the way we want it. After having additional life experience, I have concluded more and more that much of what happens to us in life is outside of our control, and I think that contributes to my increasing pessimism.

Point B right now. I owe so much to American optimism/individualism for making me so profoundly self-aware, much to the chagrin of my fellow autobots. It all seems rather relative though.

Even though I’m on a whole terribly unhappy, I do laugh quite often. I act hysterically/comically (for the love of it and of course as a desperate cry for help). It’s always an oscillation of “get me the hell out!” vs. “wow, that last hour of my life was quite fun.” It always seems I have to work for my fun. Much the same way a prank may take days or months or years to set up, yet the prank itself last quite a short time in comparison.

I believe it matches your graph a bit. Point A and it’s preceding incline representing the maddening joy of anticipitation. Point A being the END of the event. The joy is never in the event because the event is too short to really grasp the fruit. The following decline involves mostly wishing you could go back in time to the point right before A and just stay there forever and ever. I think the journey to C is more of an adaptive mechanism. Your body automatically carries you through the wreckage. Being fully conscious during mental anguish cannot be healthily sustained for too long. So C is simply the flat line until the next idea of some event. If the idea never comes, one may find themselves slowly sinking again.

Much like drug use, there seems to be a diminished return with each incline. Or my entire premise is hogwash. If I could dress in winter the same way I do in summer, I wouldn’t mind point B as much. It’s always those small irritating external factors that seem to ruin everything about the joys of low self-worth.

“Your body automatically carries you through the wreckage.”

Many profoundly true things in your comment, but that is the most profoundly true.