Over at The View from Hell a week or so ago, Sister Y advanced a recommendation for reading Somerset Maugham‘s Of Human Bondage (1915). I frequently pass up recommendations for reading due to something of an ambivalent relationship I have with literature: I enjoy it enough, but at the same time I have embedded in my consciousness a sense that reading “good books” serves primarily as a device for signaling one’s membership in a high-status, educated elite. (Runs in the family: my mother for a long time put a cartoon from the New Yorker on her refrigerator. A well dressed woman speaks to a bookstore clerk: “Just something for the beach, but I did major in English.”) This fact makes me wonder if literature is a good use for my time. But the fact that it’s Sister Y abates my skepticism, and I read the book.

Well worth it. Really well worth it. As an illustration of how ordinary life can be (is!) filled with heartbreak and frustration, Of Human Bondage has few literary peers, so I can second Sister Y’s recommendation. Our hero, Phillip Carey, is orphaned, fails in romance, fails in in his preferred career, fails to achieve his life objectives, encounters shocking deaths (one a suicide, the other one of an innocent child), and naturally endures no small amount of suffering and humiliation in his own right. It’s a fine remedy for unwarranted cheerfulness, which is to say, most cheerfulness.

Sister Y, in her post, concentrates on the image of a Persian rug and its meaning, pursued throughout the novel. That’s a trope well worth pursuing. But what struck me were two sentences very near the close, as the hero realizes that he’s just not going to realize his hopes for his life.

He thought of his desire to make a design, intricate and beautiful, out of the myriad, meaningless facts of life: had he not seen also that the simplest pattern, that in which a man was born, worked, married, had children, and died, was likewise the most perfect? It might be that to surrender to happiness was to accept defeat, but it was a defeat better than many victories.

After all the disasters Phillip (who is apparently thinking these sentences) has been through, what’s magnificent is how false this rings. The final sentence in particular is a sentimentalism, a cliché, the sort of thing you would expect to find not in a serious literary novel but in a self-help book or on an inspirational plaque in somebody’s middle-class kitchen. This is a use of irony, one of a special kind for which I think there must be a more technical term where a sentimental cliché is asserted at the end of a tragedy. By being son unequal to all that went before it, the nominal sentiment it expresses is actually being mocked. Call this the irony of the closing cliché, for lack of a better term.

The irony of closing cliché is an old, old game in literature. I was reminded of an ancient poem — possibly one of the oldest in English, at least in parts — conventionally known as The Wanderer.

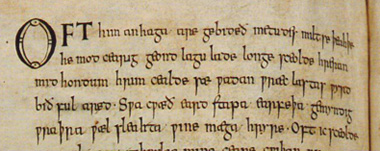

I’ll spare your eyesight. It opens like this.

Oft him anhaga are gebideð,

metudes miltse, þeah þe he modcearig

geond lagulade longe sceolde

hreran mid hondum hrimcealde sæ,

wadan wræclastas. Wyrd bið ful aræd!

I suppose there are many possible translations, but here is mine.

Often the solitary man awaits mercy,

Or the favor of a lord. Though he, heartsick,

Must long through waters turn his oars (lit. his hands)

In icy seas, going the path of exile.

And fate is unmoved.

And onward through 100 or so lines describing the narrator’s loss of everything he ever cared about and his being driven into exile. But at the end

Wel bið þam þe him are seceð,

frofre to fæder on heofonum þær us eal seo fæstnung stondeð.

That is,

Better for him that seeks mercy,

Consolation from Father in Heaven where for us all safety rests.

I guess those lines ought to be on someone’s kitchen plaque as well.

8 Responses to “Wyrd bið ful aræd!”

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.

I really am astounded at how some works managed to get past the censors in those days. My theory on why this passage was (I have not read the book) was based mainly on the work needing to acquire the editor’s approval – but still, when works like de Sade’s got published, I guess I’m probably wrong in this view.

I’m also told that this poem has 666 words in it (I havn’t tried counting them myself). Make of that what you will.

Maugham had a child, I believe, Make of that what you will. The novel is largely autobiographical; he had a stutter instead of a foot deformity.

Interestingly enough, he also wrote a short story about a girl who kills her child immediately after it’s born (she doesn’t have access to an abortion), though not out of concern for the child, exactly. It’s called The Unconquered.

And another tidbit from Maugham’s Wiki page: “Maugham’s mother Edith Mary (née Snell) was consumptive, a condition for which her doctor prescribed childbirth.”

This infuriates me to no end. And doctors still do that, too. After talking to my GP, I’m convinced she’s one of them.

Prescribed chidlbirth to a woman with consumption?

I’m glad I didn’t read that before going to bed last night. It would have been very hard to sleep.

I’m gratified that you read Of Human Bondage!

There are probably hundreds of examples of pieces of literature that have “escaped the censors” and been kept in our canon despite containing massively antisocial sentiments, saved by a miserably transparent cliche at the end. I like your examples – a couple others would be the miserably cheery alternate ending of Great Expectations (with the flowers growing in the cracks, as I remember) and the book of Ecclesiastes. The shout-outs to God in Ecclesiastes are so hollow and snicker-worthy compared to the mature text that I’ve read they were inserted long after the writing of the text.

The last chapter of Job has a pretty tacked-on feel about it, too.

I really like how you guys are atheists (I’m assuming) and yet still read the bible for its own merit. I’ve never really seen a proper atheistic book review for the Bible that treated it as a short story collection etc., but if I find the time, I might do one myself as soon as I’ve read the rest of the Old Testament. From what I’ve read so far, I’d say the genre it’s in is probably a cross between Horror and Fantasy.

Totally worth reading: Willis Barnstone’s translation of the gospels. I love the King James Version, but Barnstone’s translation (especially with his notes) is now my favorite. Pretty sure he’s an atheist, as are probably most serious scholars of religion.

My take on Job…